Litreview

Literature Review

This literature review analyses the most relevant literature on the development methodology used to build Digital Twins for chemical industries. First, the concept of a Digital Twin is more formally introduced. Then, the design process of a number of Digital Twin Systems is compared to show the common elements and challenges in building a digital twin system. This provides a foundation for the use case of a DT development system.

Digital Twins are complex systems, and are built on a variety of technologies. The majority of the Literature review discusses the technologies used in the various case studies, and how they could be more broadly applied in building DTs. To ensure that the framework for building DT systems is able to work well with real-world tools, existing standards for Digital Tools are discussed. These are evaluated based on how useful they are to DT systems.

An Overview of Digital Twins

Digital Twins are a broad concept that has been used in many disciplines. It was introduced by Michael Grieves as a way to utilize the wealth of data avaliable from modern digital systems in a way that helps us replicate, visualise, and analyse the physical system without the constraints of the physical realm [@grieves2014digital (Private)].

The term "Digital Twin" is used in a variety of industries. In construction and smart cities, DTs of buildings are used for planning, construction and operation, and to keep track of changes over time - a natural extension to traditional floor plans. In Healthcare, "Digital Twins" are used for personalised medicine prescription. In Manufacturing, Energy Generation, and Aerospace, DTs are used for performance modelling and fault analysis. In Robotics and Automotive industries, DTs are used for real-time decision making, simulation, and training [@applications_singh_2022 (Private)].

The broadest definition of a Digital Twin is a set of digital data that mirrors a physical object or system. Different authors have interpreted this differently, and the usage of the word differs across industries. Michael Grieves categorized Digital Twin Development in phases, where the simplest forms of Digital Twins only modeled the form of a product, and more advanced DT systems modelled behaviour, could integrate with other systems, and could use the data to make predictions and act autonomously [@grieves2023digital (Private)]. In other literature, it is strongly associated with the concept of bi-directional communication between a physical and virtual model [@agrawaldtconcepttopractice (Private)][@KRITZINGER20181016].

![Digital Twin System Classifications (See also [@WALMSLEY2024100139], [@energy_yu_2022] and [@applications_singh_2022] )](/thesis/assets/dt_focus.drawio.png)

In the field of Chemical and Process Engineering, Digital Twins are most commonly associated with high fidelity behavioural modelling, and bi-directional communication, [@energy_yu_2022 (Private)]. A whitepaper from ArcWeb differentiates between "Project Digital Twins" used for offline analysis in design and construction, and "Performance Digital Twins" used for operations and maintenance. A DT system could be made or adapted for either, but bi-directional communication is a characteristic of Performance Digital Twins by nature of requiring a physical system running at the same time. This article will focus on this kind of Digital Twin system, though the attributes of Performance Digital Twins and Project Digital Twins strongly intersect.

Digital Twins from a Control Perspective

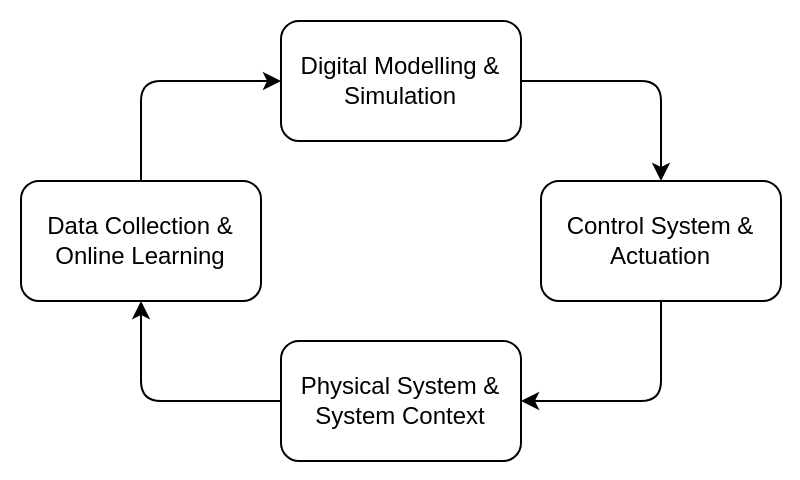

The bi-directional communication of an autonomous Digital Twin can be better viewed from the perspective of control systems. The fundamental characteristics of such a Digital Twin include:

- Physical System & Context Awareness: This type of Digital Twin represents one physical system - i.e., the specific physical object must be identifiable [@minerva_digital_2020 (Private)]. It also may represent the environment of the physical system.

- Real-time Updates through Data Collection and Online Learning: Digital Twins are updated as often as necessary to reflect changes in the physical system. It also stores and updates some "state" that defines key attributes of the physical system.

- Digital Modelling and Simulation: Digital Twins incorporate models—mathematical, machine learning, or hybrid—that represent the system's behavior and can simulate future states under different conditions.

- Control and Actuation: Digital Twins can communicate with the physical system through control mechanisms.

Together, these form a control or feedback loop, where the Digital Twin is used to predict the future state of the system, and controlling actions are tested on the Digital Twin before being implemented on the physical asset.

In this way, a digital twin can be viewed as a natural progression of existing control systems.

A Brief Survey of Digital Twin Development Methodologies

A survey by Kritzinger et al. [@KRITZINGER20181016 (Private)] found that many articles that discussed Digital Twins in manufacturing only discussed Digital Models, which do not communicate with a real plant, and Digital Shadows, which recieve data from a real system but do not communicate back. Literature that truly analysed Digital Twin systems is much more scarce, and most literature found were on the topic was reviews and conceptual models. The field is still relatively new, and designing a Digital Twin is still a complex challenge.

To gain an understanding of how Digital Twins are currently being built in Literature, this section discusses a number of recent articles published with the keywords "Digital Twin Case Study". The articles were chosen to focus on Manufacturing and Process Engineering fields, on Digital Twins used during operation for real-time monitoring, optimisation, and control. Particular attention is given to those with bi-directional communication between the Digital Twin and Physical asset.

Each paper discussed tackles the problem of building a digital twin in a slightly different way. This section aims to answer the questions "How does software and technology assist the creation of Digital Twins?" and "What challenges do current techniques face that increase the cost of building a Digital Twin of a chemical process?" by comparing the tools, frameworks, software, and standards used in each study.

Fiber Processing Plant

Azangoo et Al. [@azango_dt_pid_generation (Private)] demonstrated a methodology to generate a Digital Twin from Process & Instrumentation Diagrams (P&ID) using text recognition and image processing technologies, and a user interface to allow an engineer to link up anything that wasn't automatically recognised.

The raw file was converted to the DEXPI file format [@dexpi_summary (Private)] ^[Examples of DEXPI files and the specification can be found at https://gitlab.com/dexpi], and this was converted into an intermediate Graph Model designed to make importing and mapping operations easier. This model was then imported into the BALAS simulation software [@vttbalas (Private)], which was used for steady-state simulation. In theory, an integration could be easily written for other simulation software as well.

This is a good technique for building a Digital Twin where no digital models are already present, particularly for systems designed before the rise of Industry 4.0 techniques. It dramatically reduces the amount of manual work required to recreate the plant. Even for newer systems, using data from a DEXPI file as a starting point could reduce the cost of building a Digital Twin. However, this study focuses on building the model; interconnection with the plant's data control system (DCS) was not included.

Brewery

The application of Digital Twins to Food Processing Industries was discussed by Kolouris et al. [@KOULOURIS2021317 (Private)] using a brewery as a case study. Because of the complex chemical composition, modelling chemical and thermophysical characteristics using material and energy balances is much less feasible. However, as a brewery is a batched process, the major source of inefficiency is in scheduling. The DT focused on defining the characteristics of the plant, and the brewing recipe, so that schedules could be automatically generated. Based on live data from the plant, as soon as delays are encountered, the future schedule could be automatically recalculated from the constraints present in the Digital Twin. Uncertianty could also be modelled using Monte-Carlo techniques.

Tissue Paper Mill

A whitepaper by VTT on Process modelling and Simulation [@caro_vtt_process_modelling_whitepaper (Private)] outlines how an existing paper mill was retrofitted to cut water consuption. A reference model was able to provide a baseline of performance, and this could be validated using sensor data. This enabled greater visibility into the cause for problems, and helped narrow down the cause of water consumption so that improvements could be made. Design changes could be tested on the virtual systems before applying them to the physical systems.

Thermoforming Machine

Turan et al. discuss a case study where a DT is created using Finite Element Simulation of a thermoforming process [@digital_turan_2022 (Private)]. The DT collects data in real time from the physical twin, such as temperatures, material thickness, compressed air pressure, and deflection. It optimises those parameters that can be changed, such as the heating power load and the process timing. These are then sent to the physical twin via the Programmable Logic Controller (PLC). This was able to decrease the failure rate, and thus the material consumption.

Finite Element Modelling was performed from first principles in this study, which may not be scalable up to larger systems without the aid of other tools. However, the data collection pipeline discussed using node-RED as a tool for manipulating the various incoming data streams into a required format. This technique could be generalized to other DT applications.

Heat Production Plant

Martinez et al. discuss tracking systems [@martinez_tracking_simulation (Private)], which are used to update a First Principles model based on real-time feedback. A design-time model can be adapted by using optimisation techniques to adjust the model parameters to minimize the difference between model results and physical plant results. This can then be performed continuously as new data is collected, while at the same time the model can be used to predict future performance. OPC UA was used as the communication mechanism, because it enables both real-time and historical data access functionalities [@opc_spec (Private)].

Adjusting a model to minimise the difference between model results and physical plant results would be a common requirement of DT sytems. These techniques could systematized to reduce the cost of developing a DT model.

General-purpose High Level Control

Bellini et al. [@bellini_high_level_2022 (Private)] discussed a platform Snap4Industry that utilise OPC-UA, IoT technologies, and the Node-RED event driven architecture to create a more general purpose way of visualising and controlling industrial processes. This includes frontend tools to create displays and dashboards, store historical data, and send commands to the control network. It is posited as a method of higher level control across multiple SCADA systems.

Discussion

At the core of each of these case studies is a model of the behaviour of a chemical process. However, this model is combined with different data to adapt it to each different use case. The Brewery added scheduling data to predict optimal schedules, the heat production plant added real-time data to fine-tune parameters, and the paper mill added historical data and potential design changes to validate new design ideas.

Working with such a diverse range of data and other tools can be a challenge, which explains why most digital twin systems are custom-built to the specific use case. However, the core model is relatively similar in each case. If the core model can be reused with a variety of adjacent techologies, it will increase the Digital Twin's value and reduce development cost of each subsequent feature.

Adjacent Technologies

There are a number of ongoing areas of research mentioned or adjacent to the tools used in the previous case studies. This section summarises the state-of-the-art in each of the more frequently mentioned tools, and discusses how they are applied in building a Digital Twin, or how their application could assist in building Digital Twins of Chemical Processes.

Data Collection & History

In most cases, Digital Twin systems are real-time and thus require data to be collected from the physical system. Additionally, storing and using historical data can be useful for learning interactions within the system and its environment, which can be used to improve the Digital Twin model's ability to simulate and predict responses.

Udugama et al. break down the collection of data from process operations into the following sections [@udugama2020role (Private)]:

- Process Data, from on-site sensors, PLC control systems, IoT sensors, and SCADA systems. This can include startup/shutdown data, process control status, and physical attributes including temperatures, valve positions, vibration, or composition. This data can be collected in real time and automatically processed and stored.

- ERP Databases, a "digital logbook" of what has been processed in the past, what raw materials and inputs were used,etc. This can be used to identify stable operating conditions, and can be collected in real time.

- Engineering Data refers to historical design documents, and changes in the plant layout over time. Updating engineering data is a more manual process - it is not collected in real-time. A DT model could be considered a type of engineering data, or other engineering data could be used as source documents to build a DT model.

- Manual Logs include historical data manually recorded and not avaliable digitally. These could potentially be replaced by a digital twin of sufficient fidelity.

- Quality Logs include samples that are taken offsite and analysed, outside of normal operations. These are more complex to integrate with a digital twin, but may be used to fine-tune performance to target a specific quality.

This data is used for a number of purposes. Tools such as a Distributed Control System (DCS) use real-time data for control and understanding of past performance. This requires well structured data such as process data, and often limits data collection to what is required for a specific task. Data warehouses are used to store less structured data, but aim to be more comprehensive so any required data can be found to support future decisions [@balasko2007happens (Private)].

Digital Twins aim to augment these data sources by combining multiple together, using techniques such as machine learning, mathematical modelling, and sensor fusion, each of which will be discussed subsequently.

Sensor Fusion

Sensor fusion combines data from multiple sensors to produce a more accurate representation of the system. This can reduce noise in the data or provide more information than any single sensor can provide. For example, virtual reality headsets use multiple cameras, accelerometers, and gyroscopes to track the user's head position and orientation.

In a Digital Twin, sensor fusion can be viewed as a means to get accurate data from a process to give to the DT Model. The process measurements avaliable from the sensors may not match the input expected from a design-time model: sensor fusion can be the bridge between the two. Alternatively, the DT itself can be viewed as an advanced form of sensor fusion. Thus the architecture of the two technologies may be similar.

A simple example of sensor fusion is the Kalman filter, which combines past measurement and prediction data to get a more accurate value than either alone. It can be designed to adapt to the variance in the data, and with some adjustment can handle non-linearities quite well too [@welch1995introduction (Private)]. The kalman filter resembles a predictor-corrector algorithm, which is quite similar to the way a digital twin would be used.

Kalman filters provide a powerful example of how to update predictions based on new data, and has been used for sensor fusion in chemical processes. However sensor fusion usually involves incorporating data from distinct sensors. Lines et al. [@lines2020sensor (Private)] used multiple forms of optical spectroscopy to better estimate chemical composition of spent nuclear fuel; this was used to control the process to a set composition ratio. The model uses to estimate composition was based on partial least squares, trained on known samples. Partial least squares protects against overfitting, which is important with techniques such as spectroscopy that generate a lot of data.

These techniques can be combined with adaptive technologies such as the kalman filter to avoid degradation in online operation due to fouling and changes in process conditions [@chen2015soft (Private)]. Another common technique for adaptive sensor fusion involes using mean and variance update methodology [@wang2019monitoring (Private)], where the mean and variance is updated incrementially.

Other methods for sensor fusion include bayesian analysis, and their more generalised form, Theory of Evidence models such as Dempster-Shafer theory[@alam2017data (Private)]. These have been used in a similar way to the kalman filter, working to minimise the error or find the most likely course of events based on weighted probablilities. This has been used to fuse field measurements with simulation data [@renganathan2020aerodynamic (Private)] to decrease both bias and variance compared to either source alone.

Artificial intelligence methods can also be used for sensor fusion, but they rely on good data and can sometimes suffer at the extreme ranges of operation where there is less data. One promising technique is the concept of grounding AI methods in physics, through physics informed neural networks [@raissi2019physics (Private)] or fuzzy rules [@lermerfuzzyrules (Private)] to improve generalisation and reduce the amount of training required.

Mathematical Modelling

This involves using some kind of mathematical or algebraic formula to represent the interactions within the system or between the system and its environment. For example, thermodynamic equations can model the behavior of a chemical reactor. Mathematical models can enrich the data collected from the physical system by calculating properties that may not be directly measurable.

There are two main paradigms of note: Algebraic Modelling and numerical computing.

Table: Comparison of Algebraic Modelling Languages and Numerical Computing Libraries

| Feature / Aspect | Algebraic Modeling Languages (AMLs) | Numerical Computing Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | High-level formulation of optimization problems | Low-level numerical computation and algorithm design |

| Examples | Pyomo, JuMP, CVXPY, PuLP | JAX, NumPy, CasADi, TensorFlow, SciPy |

| Problem Representation | Declarative: equations/constraints defined like math | Imperative: custom code defines the computation logic |

| Ease of Use | Very user-friendly for optimization problems | Requires deeper programming and mathematical understanding |

| Differentiation | Mostly external or automatic via solvers | Built-in or symbolic (e.g., JAX, CasADi support autodiff) |

| Solver Integration | Built-in support for various optimization solvers | Must integrate solvers manually (if used for optimization) |

| Suitable Problem Types | LP, MILP, NLP, convex, robust optimization | General numerical problems, ODEs, PDEs, ML, simulation |

| Dynamics & Control Support | Not a core functionality, possible with pyomo.dae and gekko | Strong support (especially CasADi, JAX with custom dynamics) |

| Scalability & Performance | Depends on solver | Highly scalable with JIT, GPU, vectorization |

| Paradigm | High-level, mathematical modeling | Low-level, computational modeling |

Algebraic modelling libraries (AMLs) enable using a very high level problem specification. Variables and equations to constrain your variables are declared symbolically. Objectives can also be added to create optimization problems. The AML decomposes the system of equations and sends it to to a mathematical optimization solver. The system can be solved for any given set of known parameters. This adds a lot of flexibility as it is trivial to change which variables are unknown and which are known in the declarative model [@fragniere2002optimization (Private)].

Various AMLs have been built, both commercial and non-commercial. Historically, they have been distint languages, such as AIMMS, AMPL, and GAMS. However, more recently, open source AMLs have been built on top of existing general-purpose programming languages, such as Pyomo and JuMP, based on Python and Julia respectively. This adds more flexibility to define and build models programmatically [@jusevivcius2021experimental (Private)], and apply a variety of model transformations [@hart2017pyomo (Private)].

AMLs are helpful in chemical modelling because it is easily to directly recreate known physical equations, such a a thermodynamic equation of state, in an AML. They also work well with nonlinearities, which is required in almost all chemical systems. Some examples of AMLs used in this way include IDAES-PSE and GEKKO. IDAES-PSE is built on Pyomo, and declares a variety of reusable chemical unit models using mass and energy balances. It uses the flexibility of python and pyomo to make these customizable and composable into complex flowsheets [@lee2021idaes (Private)]. GEKKO is a seperate python-based AML that creates AMPL models internally, but has a similar library to IDAES for chemical operations [@beal2018gekko (Private)].

Because AMLs are particularly suited towards optimization, they are often used in design-time steady-state simulation in chemical engineering. However, they can also support dynamic simulation, through Differential-Algebraic Equations, which can be converted into algebraic finite-difference formulations [@nicholson2018pyomo (Private)]. Pyomo-DAE supports this, which can be used for dynamical optimization such as Model Predictive Control [@PARKER2023103113 (Private)].

Numerical Computing Libraries are lower level, and provide support for numerical transformations of data, including parallel/array computing, automatic differentiation ^[Automatic differentiation is also somtimes called algorithmic differentiation.], ODE solving, and optimization. These can be used to do much the same thing as an AML, and because they are lower level they can be optimised for a specfic use case. CasADi is an example of this. It is a symbolic framework, storing mathematical expressions similar to an AML, and it implements automatic differentiation, which is in turn used for non-linear optimisation and model predictive control [@andersson2019casadi (Private)]. It can be used for optimisation the same as traditional AMLs, especially with it's Opti toolbox, but it can also be used for initial-value problems and ODEs through an integrator, and for solving via an rootfinder. Jax is relatively similar to CasADi, with plugins for optimisation and solving, but also a strong focus on machine learning applications [@rader2024optimistix (Private)].

These libraries are better suited to solving specific problems in an performant manner, because of the lower level control that is offered compared to a conventional AML. Less has been written about using these libraries for chemical modelling, but CasADi has been shown to be useful for dynamic optimization of OpenModelica Models [@SHITAHUN2013446 (Private)] and has been used for this in JModelica.org [@magnusson2015dynamic (Private)].

Either AMLs or Numerical Computing methods could be used to model physical behavior in a Digital Twin. AMLs provide a very expressive interface that could work for a large number of cases, however to solve specific problems in a performant manner, the fine-grained control of a numerical computing library may be beneficial. In these cases, specific interfaces have been written to integrate with higher level domain-specific tools such as Modelica. The most relevant use case for Process Digital Twins is Model Predictive Control, which will be discussed further in depth.

3D Modelling and 3D Simulation

3D models can simulate physical systems, such as Newtonian physics, fluid dynamics, heat transfer, or flow. Some have considered a 3d model to be required in a Digital Twin. While it may be logical to include a 3d model in a mechanical system, the key dynamics of a process system are not visible in the same manner, and so it is not always required [@WALMSLEY2024100139 (Private)]. Michael Grieves has clarified that digital twins may only need the data necessary to represent the key characteristics of the physical system [@grieves2023digital (Private)].

Nonetheless, 3D models may still provide value in some areas of digital twinning. Computational Fluid Dynamics is a very powerful method of modelling fluid flows in 3D. It is compuationally costly, but can be used for a variety of tasks such as identifying suspected leakage positions in a fluid flow, and surrogate models can be made to speed up computation in an online setting [@gbadago2023exploring (Private)]. This can then be visualised in 3D.

Other uses of 3d modelling in chemical digital twins include augmented reality (AR) applications, where plant data from the digital twin can be overlaid onto the physical equipment, limiting the need to manually match between P&ID diagrams and the real items in the factory [@gao2022process (Private)]. Some initial work into automatically merging 2d and 3d digital plant information has been performed, by raising the abstraction level of each and matching the structure [@sierla2020integrating (Private)]. Another anticipated benifit of 3D modelling and AR is interpretability, as simulation results from the digital twin may be easier to understand and put in context of the real world.

These applications are not as fundamental as modelling the first-principles thermodynamics of a chemical process. Thus, 3d modelling can be considered not as high priority as thermodynamic modelling when building a digital twin of a chemical process.

Control

Control theory is a well-established discipline. The simplest form of control is open-loop control, where actions are sent to a system and no feedback is recieved of the system response. However, closed loop control, also known as feedback control, is used for virtually all non-trivial systems. This process involves adjusting controlling signals based on changes in a desired setpoint. The model to adjust controlling signals based on feedback can be arbitrarily complex. In the real world, the most common control algorithm in process systems is Porportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control, where the strength of the controlling action is determined based on the deviation from the setpoint, the integral of the deviation, and the rate of change of the deviation. This is a simple and effective method of control, but it can be difficult to tune for complex systems, and sometimes unstable [@svrcek2014real (Private)].

More complex methods of control include fuzzy logic control, statistical process control, artificial intelligence methods, and model-based control, including model predictive control [@kano2010state (Private)]. Control systems often work at multiple levels, with simpler control systems handling individual parts of a process, and supervisory control systems used to control setpoints and parameters of the simpler control systems, based on higher level objectives [@mesarovic1970multilevel (Private)].

If a Digital Twin is to accurately model the response of a system, it also needs to model the control system present in the system. This is often possible with modelling software for simple control methods [@burgard2023multi (Private)]. If the control system is a piece of software, it may be possible to duplicate the controller model into the digital twin so that the control systems are identical. This allows to accurately model the behavior of the physical system, which is important for accurate prediction [@he2021digital (Private)].

Control systems are similar to Digital Twins, because they also have bi-directional data communication, recieving data from a physical system and responding with corrective actions. A digital twin can be viewed as a form of Model Predictive Control, as it is used to control the physical system by simulating the effects of different controlling actions and choosing the best action to apply. For example, a DT can model a process and a control system, and calculate the appropriate parameters for the control system to perform optimally. This is also an example of multi-level control.

Because Digital Twins and Control systems are so closely linked, control systems can be used as a model of how to understand, interpret, and interact with a digital twin. The lines often blur between the two, and many digital twin tools that exist are simply repackaging of existing process simulation or control tools that have been on the market for decades [@gao2022process (Private)]. Nonetheless, software development is an iterative process, and using conventional control systems does provide a good architecture to begin designing advanced digital twin techniques.

Machine Learning

Machine learning techniques provide an alternative to first-principles modelling to predict behaviour in a Digital Twin. They have been sucessfully used as the basis for a variety of digital twin applications in Chemical process engineering, such as to predict properties such as product yeild [@nasruddin2023machine (Private)], for control purposes [@min2019machine (Private)], or for optimisation [@song2024digital (Private)]. Because of the wealth of historical data often avaliable in these industries, machine learning methods are often able to scale to more complex problems than traditional mathematical modelling. The problems of data cleaning and preprocessing, often required as an initial step for machine learning, are also required for digital twins, so it is easy to adapt a machine learning workflow to a Digital Twin context.

Some problems with machine include unbalanced datasets - a factory will generate a lot of data on normal operating conditions, but much less data on unusual operating conditions. Careful design of the machine learning methodology can decrease this issue. Data sampling techniques such as COVERT [@SEVERINSEN20241 (Private)] aim to mitigate this problem, and physics-informed techniques also improve generalisation in these areas [@raissi2019physics (Private)].

Table: Summary of machine learning techniques relevant to Process Digital Twin Modelling

| ML Contribution Area | Problem it addresses | Relevance to Digital Twins |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Modelling | Complex mathematical models can be expensive to solve, and may not capture the nuances of the real world. | Enables real-time prediction of the factory, and fine-tuning of models on real data. |

| Physics Informed Machine Learning | Generalisation of models outside training data | Helps the Digital Twin behave sensibly in abnormal process conditions |

| Online Learning | Models gradually becoming less accurate over time due to concept drift | Accounting for slow changes in the process, such as fouling or different qualities of source material |

| Function/Sequence Learning | Modelling the effect of a function, or a sequence over time | Modelling dynamics in a process, for prediction or model predictive control |

Surrogate Modelling

Another way machine learning is utilized is in surrogate modelling, where a mathematical model is used to generate data that a machine learning model can be trained on. This can be done for a variety of purposes. Surrogate modelling often reduces computational cost if the mathematical model is very complex, by using simpler functions and distilling it down into the most important aspects for the current problem. It also can make solving and optimisation easier, as a mathematical formulation that is not easily differentiable can be represented by a much easier to differentiate function. It can be used as a way to linearly approximate non-linear dynamics. Finally, surrogate models naturally lend themselves to fine tuning on real data, and are more flexible to adapt to nuances in real-world performance than a first-principles mathematical model, capturing behaviour that the mathematical model could not express [@costa2024adaptive (Private)].

Physics Informed Machine Learning

Physics Informed Machine Learning is a regularisation technique that has become popular in recent years for scientific Machine Learning applications. The general method involves adding a term to the loss function to represent the physical properties of the system, such as that energy is conserved. If the model is trying to predict a result that does not follow the physical properties we would expect, the error will be large. The main application of this technique is to increase generalisation outside the generally avaliable training data [@LIdtbeyondroutineoperation (Private)]. This increases the robustness of the model, as it provides more assurance that it will perform in a sensible manner in abnormal conditions. It is likely a key technique required to increase trust the output of a Digital Twin based on Machine learning techniques.

Online Learning

In Machine Learning, Online Learning refers to updating a model in real-time as new data comes in, without human input or retraining from scratch. This can encode changes in the state or behavior of the physical system, such as degradation of a battery. Digital Twins are generally understood to adapt or evolve alongside their physical counterpart as the physical twin changes, and online learning provides a good way to enable this [@rebellodigital (Private)]. A common workflow to build a Digital Twin using online learning is to generate a surrogate model using synthetic data from a mathematical model, then use online learning to update the model when real-world performance deviates from what the surrogate predicted [@costa2024adaptive (Private)].

Machine Learning for Dynamic Systems

Dynamic Systems pose additional problems for machine learning methods, as rather than learning outputs at a single point, results across the time domain must be modelled. Being able to model dynamic behaviour is an important predictive behavior of a digital twin [@grieves2023digital (Private)], and it enables other technologies such as Model Predictive Control.

If mathematical models of the systems dynamic response, e.g transfer funtions, are avaliable, then parameter estimation techniques can be used. This has been shown to be effective in process digital twins [@costa2024adaptive (Private)]. Bayesian uncertainty modelling can be used to formulate an optimisation problem to maximise the likelihood of the result. There are packages such as IDAES's parmest that can automate this process [@KLISE201941 (Private)].

If mathematical models of the dynamics are not avaliable, there is a growing body of research into modelling function dynamics. These include neural ODEs and ResNets [@zhang2020approximation (Private)], neural implicit flow [@nasim2024usingneuralimplicitflow (Private)], and Deep Operator Networks [@lu2021learning (Private)]. These are all based on the universal approximation theorem of operators, which is a generalisation of the universal function approximation theorem for standard machine learning techniques. In other words, while normal machine learning techniques approximate a function transforming data to data, operator networks approximate an operator transforming an input function to an output function. This enables modelling the solution to a partial differential equation or other dynamic system. They are often faster than solving a complex system of equations, so they can be effectively used as surrogate models [@kobayashi2024deep (Private)]. However, these techniques are still relatively new, and little has been done to apply them to Digital twins, A recent paper discussed using them for digital twins of nuclear energy systems, but further work is required to overcome the limitations with current operator network architectures and evaluate performance [@kobayashi2024deep (Private)].

Virtualisation / Emulation

Virtualisation is similar in concept to a Digital Twin. It is the ability to create a piece of digital software that can replicate how a physical system would behave. It is comonly used in computers and networking, as well as in IoT: A virtual computer can run the same code as a physical computer, and a virtual sensor can respond in the same way that a physical sensor can [@khan_virtualisation_wireless (Private)].

Virtualised systems may not have a single, identifiable real-world counterpart in the same way as Digital Twins. However, the ability to accurately simulate a physical system is essential to Digital Twins, so many concepts and tools can be applied from this field.

For example, a Digital Twin could emulate a physical sensor, PLC system, or SCADA system, sending data to the same visualisation and control tools that the factory uses to monitor the physical system . This would enable operators to view the simulations' response to changes in the same way as they would view the real process's responses [@sixlayer_redelinghuys_2020 (Private)], and would enable the digital twin to communicate with outside systems through already-standard protocols.

Multi-Agent Systems

Broadly, Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) include multiple distinct agents, or independently acting subsystems, that can communicate or interact with each other. A digital twin may be designed as a multi-agent system, i.e the DT is composed of many smaller agents. This can be done using e.g an ontological approach, where each small agent is responsible for gathering and providing a small amount of data for an ontological (semantic) model [@zheng2020quality (Private)]. These can be linked and queried together using protocols such as the Web Ontology Framework (OWL) or the Resource Description Framework (RDF) [@sengupta2014web (Private)], or all the results can be stored together in a nonstructural database.

Alternatively, a DT may be designed as an agent in a multi-agent system. In this case, a DT is designed with specific goals and objectives that it needs to fulfil, and it is able to interact with other agents to fulfil its objective [@pretel2022multi (Private)]. Multiple Digital Twins could be networked together to interact with each other as agents - this can provide a natural way to manage scalability and complexity [@kalyani (Private)]. Finally, a DT may provide the environment for a MAS - multiple agents may use the DT as a knowledge base to fulfil their objectives. Digital Twins could also interact with other agents in a multi agent system on behalf of the physical system, a use case similar to virtualisation.

In manufacturing and industry, the largest use case of Multi-Agent Systems in relation to digital twins is by using multi-agent systems to build a digital twin [@kalyani (Private)]. Further research is required into how other methods of using multi-agent systems could be used in Digital Twins for Chemical and Process engineering.

Standardisation Efforts for Digital Tools in Process Engineering

This section reviews some of the major standards and tools used in describing chemical processes. This provides an overview into the practical usage of the aforementioned adjacent technologies that could be useful in building a Digital Twin, and discusses how the tools and methodology that are currently used could be adjusted or generalised for digital twins.

Standard tools mean that there is a standard methodology for the task the tool accomplishes. In theory, a Digital Twin based on a combination of standard tools will already have much of the fundamentals implemented. It would also have a lower barrier to entry, as the industry will already be using those parts of the system.

To aid discussion, the standardisation efforts have been broken down into three parts:

- Standards for describing structure: These are standards for describing the structure of a chemical process, such as the layout of a plant, or the relationships between different components. This includes both 3D models and 2D diagrams.

- Standards for modelling behaviour: These are standards for describing the behaviour of a chemical process, such as the thermodynamics of a chemical reaction, or the dynamics of a reactor. This includes both first-principles and data-driven modelling.

- Standards for communication: These are standards for facilitating communication between different systems and components in a chemical process, ensuring interoperability and data exchange.

A Digital Twin system is likely going to need to build on top of standards in each of these areas.

Standards for Describing Structure

| Standard | Type | Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Twins Definition Language (DTDL) [@azure_dtdl (Private)] | IoT, NGSI-LD , Data Aggregation | Azure Digital Twins [@nath2021building (Private)] |

| Smart Data Models (SDM) [@smart_data_models (Private)][@fiware_digital_twins] | IoT, NGSI-LD, Manufacturing, Data Aggregation, Smart Cities | FIWAREBox [@fiwarebox (Private)], Sara [@sara_purpleblob (Private)] |

| JSON-LD, RDF, OWL, SHACL | IndustryFusion Digital Twin [@industryfusion_digitaltwin (Private)] | |

| DEXPI [@dexpi_summary (Private)] | P&ID, 2D, XML, ISO 15926 | Autodesk, Aveva, Bentley, Intergraph, Siemens , Cadmatic [@cadmatic_dexpi (Private)], Simantics Apros 6, Balas [@simantics_dexpi (Private)] |

DTDL, SDM, and DEXPI are all related to the Resource Description Framework (RDF) format, a method of describing the structure of and exchanging graph data [@candan2001resource (Private)]. ISO 15926 standardised an ontology for describing different resources in the process industry, including unit operations and equipment characteristics, both across space and time [@15926 (Private)]. JSON-LD and NGSI-LD are specific formats to communicate RDF data. However, different specifications built on top of JSON-LD and NGSI-LD may not be compatible, if they start with different ontologies.

Each of these services have a slightly different focus. DTDL focuses more on collecting data from sensors, while DEXPI focuses more on describing the relationship between operations. A DT that is able to read or communicate via these formats will have increased interoperability with other systems, potentially speeding up development time through greater reuse of existing models and tools.

Standards for Modelling Behaviour

| Standard | Type | Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Modelica [@modelica_specification (Private)] | Equation Oriented, First Principles, Dynamic | OpenModelica, IDEAS [@ideas_modelica (Private)] , Modelon, Dymola |

| Pytorch & other ML Platforms | Data Driven Modelling | Various |

| Functional Mock-up Interface | Co-simulation | Simulink, OpenModelica, Wolfram SystemModeler |

| CAPE-OPEN | Co-simulation | ASPEN, DWSIM, gPROMS, COCO |

| PYOMO | Equation-oriented, First Principles, Optimisation | IDAES-PSE |

Modelica is a relatively established standard for modelling physical systems. It is a custom object-oriented textual description format, that is supported by a variety of applications. The relationships between systems can be specified mathematically or externally, to model system dynamics across time. Because of it's standardisation and a variety of open source libraries, including for thermodynamic properties [@multiphase_mixture_media (Private)] and various process unit operations [@ideas_modelica (Private)].

Alternatively, data-driven approaches can be used to model chemical processes, without relying on any first principles model at all [@SAVAGE202073 (Private)]. This can have problems with generalising outside normal operating conditions, but techniques have been adapted to minimise this issue [@SEVERINSEN20241 (Private)]. Data Driven models have the benifit of being easy to create, and work well for complex systems where traditional first-principles simulation doesn't work, as long as their accuracy and generalizability is sufficient for the requirements of the application. Any machine learning platform, such as PyTorch, could feasibly be used for this. However, Data-Driven tools can also be used to augment traditional first-principles simulation [@ceccon2022omlt (Private)], so each technique can be used as best suits a given application.

The Functional Mock-up interface is a specificaton and data format that provides a standardised interface for defining a dynamic model [@blochwitz2011functional (Private)]. A Functional Mock-up Unit (FMU) can include custom C code internally to represent the behaviour, and a standardised XML interface for linking up with other components. This enables model exchange, and co-simulation using models built in seperate tools. This technology can be used to make digital twins compatible with other systems [@laine2024digital (Private)], or to make a digital twin using multiple different simulation platforms.

CAPE-OPEN is a similar interface for co-simulation between multiple simulation tools [@belaud2003missions (Private)], but does not provide a standardised model exchange format. Nonetheless, it is supported by a variety of simulation platforms.

Pyomo is a algebraic modelling language in python. IDAES-PSE is a process simulation tool that is built on top of it. Pyomo uses optimisation methods to solve a flowsheet, rather than traditional sequential solution algorithms, which makes it expressive enough to solve a wide variety of problems. The IDAES Library includes a number of different unit operations and thermodynamic property packages. Because the model is specified in Python code, interoperability with existing systems is much harder, though some research has shown that it is possible to interface Pyomo with Modelica models through Functional Mockup Units [@gohl2024steady (Private)].

Standards for Communication

| Standard | Type |

|---|---|

| OPC UA | Industrial Automation, Data Communication, Real-time and Historical Data Access |

| Modbus | Industrial Communication Protocol, PLC Communication, Serial and TCP/IP |

| Ethernet/IP | Industrial Ethernet Protocol, Real-time Control, Device Communication |

| Foundation Fieldbus | Process Automation, Distributed Control Systems (DCS), Field Device Communication |

| HART | Process Instrumentation, Smart Device Communication, Analog and Digital Signals |

| MQTT | IoT, Lightweight Messaging Protocol, Publish-Subscribe Model |

| REST/HTTP API | Web Services, Data Exchange, Cloud Integration |

Modbus [@thomas2008introduction (Private)], Foundation Fieldbus [@vincent2001foundation (Private)] and HART [@hartprotocolgajera2024 (Private)] are examples of low level communication protocols, designed for the interface between field devices and control systems such as PLCs. These can vary widely depending on the equipment used in the factory. They are likely too low level for a general-purpose digital twin solution, as most of the DT case studies discuss a DT operating on a scale similar to a SCADA system, or broader. However, they may provide a way for a DT to communicate back to a PLC - a DT could use virtualisation techniques to emulate a hardware device and create a "soft sensor", similar to what is discussed with sensor fusion. These protocols could also be used to emulate the entire sensor network, to simulate the response of the PLC and scada system in various conditions.

OPC-UA [@opc_ua_technologies (Private)] and Ethernet/IP [@lin2013inside (Private)] both are generally applied higher up, in SCADA systems at the supervisory level. They are more able to scale up to larger systems with many devices, across multiple networks. They provide a more general framework for accessing data from a variety of sources, and giving controlling signals to PLCs, and are used in the digital twin case studies previously discussed. These protocols will be the main interface with a DT system. It should also be noted that OPC also includes a standard to access historical data, which would be of use to Digital Twin Systems [@bochenek2011opc (Private)]

On the highest level of abstraction are more general-purpose technologies such as MQTT and HTTP APIs. MQTT is rising in popularity with the introduction of industry 4.0, particularly because it enables more general purpose databases for backup and historical retrieval. It also enables general purpose visualisation technologies to be used seamlessly in industrial settings [@RIEDEL2022601 (Private)]. Likewise, techonologies such as REST APIs and Websockets are used to enable other high-level dashboards and enterprise visibility [@bellini_high_level_2022 (Private)]. They could also be used for getting specific use-case related views of the entire system, as discussed by Kulger et al. [@kugler2021method (Private)]. A DT could also provide similar APIs, to enable other tools to be easily built using it.

Backlinks